To most people, it resembles Justice Potter Stewart's description of pornography - they know it when they see it.

If you pushed most of these people to describe what approximately it is that causes them to see it, they would likely have the sense of someone trying to manipulate public opinion for selfish political ends, to encourage conformity in viewpoint and values, particularly with regard to biased or untrue viewpoints.

But how exactly do we distinguish propaganda from public service announcements, or statements of shared values, or celebration of historical symbols and rituals, or any other number of related concepts?

One of the good lessons I remember from reading Less Wrong back in the day is the general pointlessness of arguing over definitions. If you're tempted to argue over what is or what isn't X, you're almost certainly better off just redefining X into its component pieces, and just saying what corresponds to what.

So to me, there is one concept that can be defined in fairly value-neutral terms - attempting to influence public opinion. This covers a wide range of the examples above.

And layered on top of that is the pejorative sense - the perceived bias or bad faith of the messenger.

This latter part, of course, is mostly where people disagree.

And so in this sense, what people perceive as being propaganda is a far more interesting question.

As is often the case, one google image search is worth a thousand essays on the subject (see, for instance, here).

So here are some:

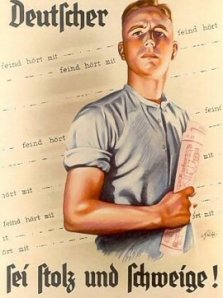

Propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda

These are just some samples. Your own image search will work just as well.

As always, it is a useful corrective to let data change your mind, even just if in small ways. My guess ahead of time was that the strongest association with "propaganda" would be "Nazi", but none of the images on the first pages are German. I didn't expect nearly as many American entries, but then again this might just reflect the preference for being able to easily understand the text.

So what are the common themes?

The overwhelming principle is that people perceive propaganda as being mostly from World War 2 and the surrounding era.

One potential explanation is Moldbug's observation that the propaganda of the 30's and 40's was particularly crude (he cites this video as an example).

There's a certain truth to that. The images definitely look dated. But I suspect a large part of this is just that they use paintings where today we would use photographs, the fonts aren't computer-rendered, and the voiceovers emphasise the neutral mid-Atlantic broadcaster pronunciation. If you had given Goebbels some rudimentary training in Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft Video Editor, I doubt it would have taken him long to get equally slick, modern-looking production values.

The small number of modern examples that show up are actually the most revealing. The two that seem to register as being of the same class tend to ape the old poster designs, with Soviet-style drawings, bold clashing colours, and over-the-top symbolism. In this regard, you usually have to be quite overt to trigger the propaganda label.

But there's another aspect here that ties together the past images and the small number of present images.

To wit: people only view things as propaganda when they don't actually share the viewpoint being pushed.

To share the underlying viewpoint is to suspend one's disbelief about the nature of the messaging, and the desire to convert the unbelievers. One cannot see the strings being dangled and the puppets being manipulated, because when one believes the same thing, they simply come across as the truth. The truth needs no justification other than itself. Hence anybody pushing it is not trying to influence the rubes in the general public, they're just delivering a genuine public service.

In this regard, the images above may seem strange at first glance - why are there so many American examples? The answer, I think, is that the cultural values of America in World War 2 are almost as alien to us as those of the Soviets of the time. Which is why crude racial caricatures and related national symbolism seem so jarring today. They are aimed at an audience that is very different from modern Americans, and so it's easy to perceive the messaging.

And crucially, the only modern examples which show up are those covering the most partisan political issues.

Donald Trump in front of an American flag is propaganda, if you are a Democrat.

A Muslim women wrapped in an American flag as a hijab is propaganda, if you are a Republican.

But no Republican would have the first spring to mind as a symmetric example of propaganda, and no Democrat would think of the second.

Which makes one wonder - what are the types of propaganda that (at least in polite society) don't have an opposing partisan to point them out? What are the things that, in David Foster Wallace's wonderful essay, are simply the water that we swim about in and don't even notice?

Or equivalently, what are the opinions that are taken for granted today, but which might be seen as propaganda by people in 50 or 100 years? These ideas almost certainly share a lot of overlap with Paul Graham's idea of "What You Can't Say". But sometimes it's not just things you'd get massive flak for disagreeing with, as just things most people wouldn't think to disagree with.

When I tell you to imagine "Communist propaganda" or "Nazi propaganda", you can picture an image.

When I tell you to imagine "Republican Propaganda" or "Democratic [Party] Propaganda", you can probably do the same.

But when I tell you to imagine "Democracy Propaganda", especially if I limit you to modern examples, your mind draws a blank. There is no cached entry there.

Isn't that strange?

When I tell you to imagine "Communist propaganda" or "Nazi propaganda", you can picture an image.

When I tell you to imagine "Republican Propaganda" or "Democratic [Party] Propaganda", you can probably do the same.

But when I tell you to imagine "Democracy Propaganda", especially if I limit you to modern examples, your mind draws a blank. There is no cached entry there.

Isn't that strange?

Sometimes, it's helpful to proceed by way of analogy. So let's start with an example that we can all now look back on as having an enormous propaganda aspect - the Nazi concept of Aryan.

Aryan Propaganda

Aryan Propaganda

Aryan Propaganda

With the benefit of hindsight, aryanism is a strange concept. It conveyed a sense of the canonical blue-eyed, blonde-haired German ethnic pride. It managed to be a hybrid mix of appearance, nationality, ethnicity, and character. It was an amorphous ideal that somehow conveyed positive connotations from ideas of racial uniformity, especially as applied to Germans and Nordic-looking people. Given its many uses, providing a concrete definition is non-trivial, let alone the difficulty of trying to explain why exactly aryanism was meant to be a good thing.

You can see this water. You can understand it intellectually, as an anthropological phenomenon. But it is utterly alien. You simply cannot see it as a German in 1941 would have seen it.

So, the question is - is there a modern equivalent of aryanism?

Is there a term that most Americans understand with approximately the same sense that Germans understood aryanism in 1941? Maybe there isn't one. Maybe modern readers, so inured to the constant bombardment of marketing images, couldn't possibly fall for such a peculiar and loaded term.

One possible answer is below the fold.